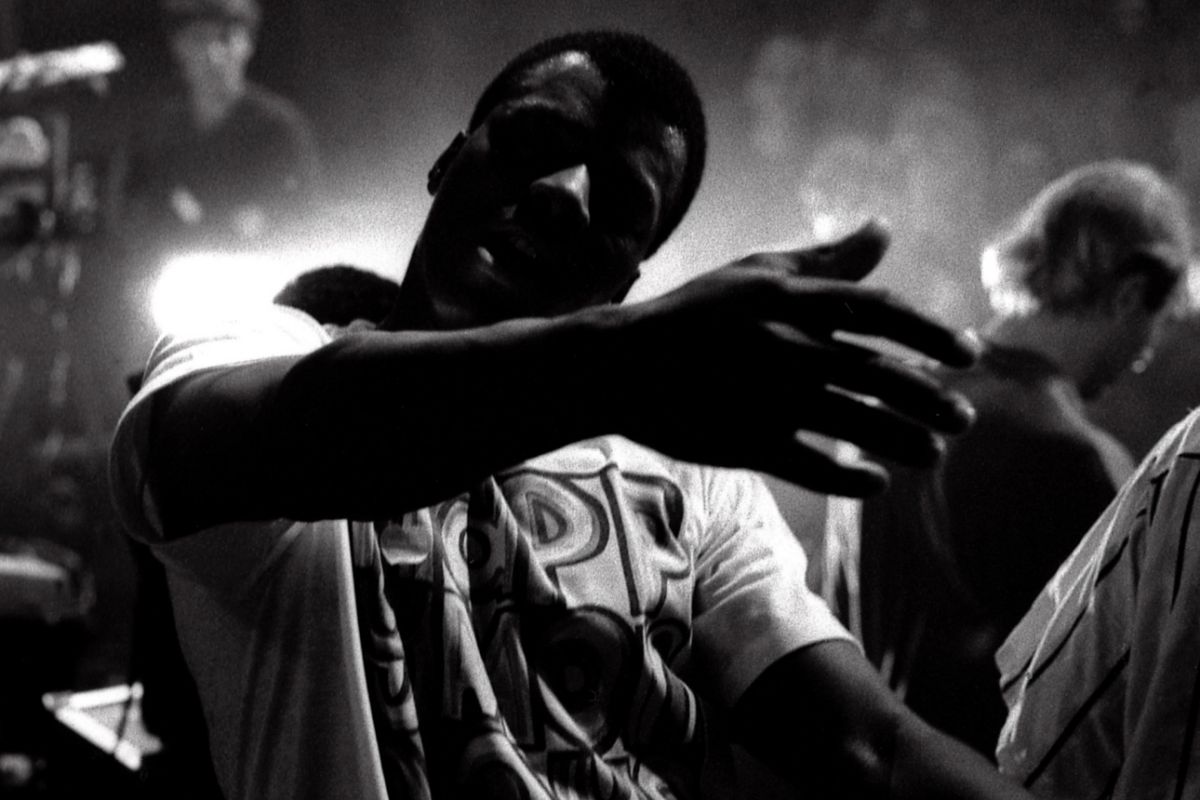

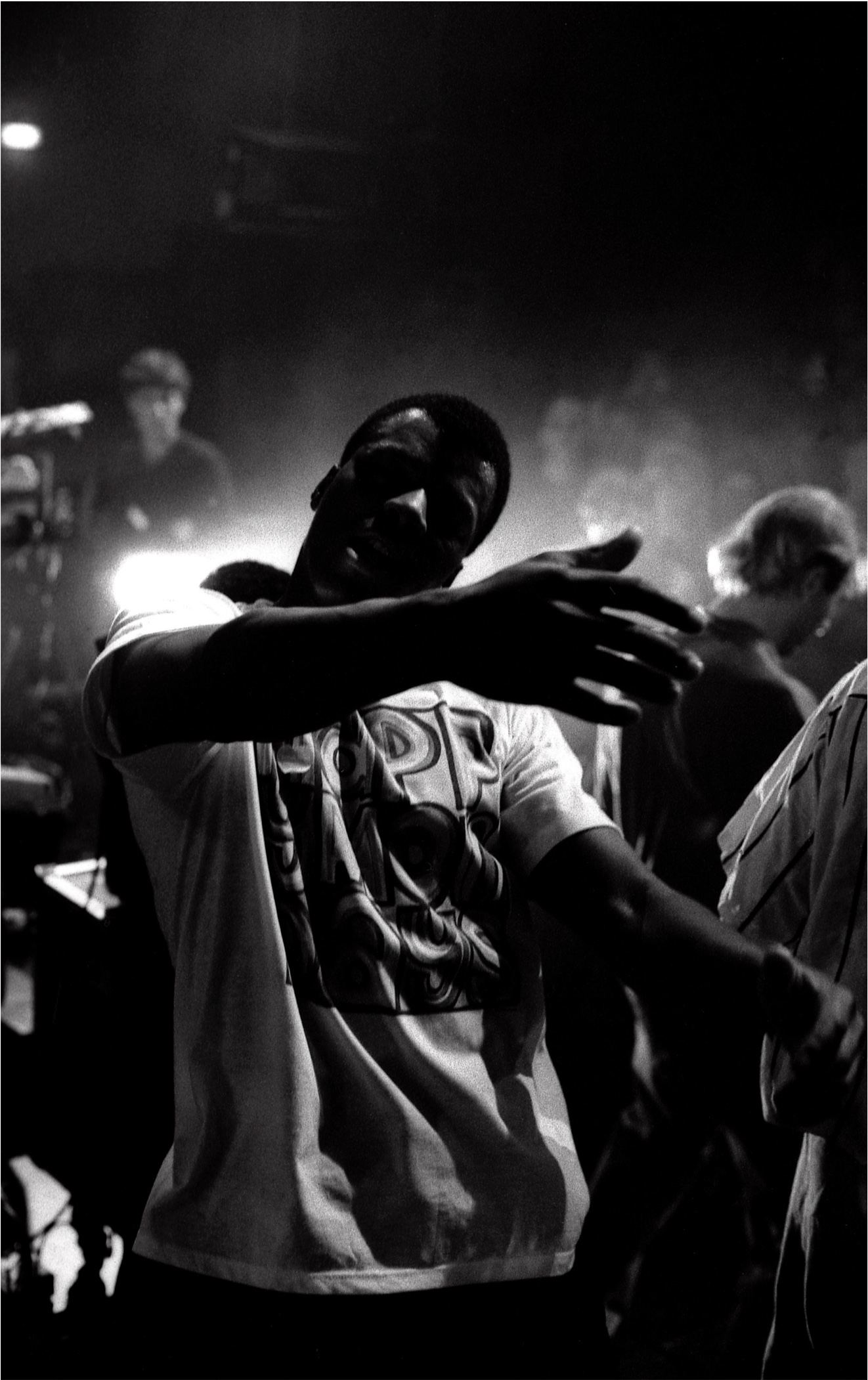

We are a dancing nation because of the youth. The world is always changing and those in charge of the future – young people – will generate culture that reflects their reality. And so, in the final decade of the last millennium, it was people in their mid-teens to their early twenties who used their feet to expand and create new culture in repurposed dance spaces. We were adding a new verse to an old song, and we did so at scale.

“Dancing with other people isn’t passive, it is active, and it can create action: buying records or making music for fellow dancers; or creating a space where people can dance for the allotted five hours before tumbling out of the exit and looking for more.” Emma Warren

Collective ways of dancing change over time. Sometimes it crests generationally, like at the infamous marathons of Depression-era North America when couples would dance for hundreds of hours for cash, or at the highpoint of a cultural moment at, say, Quadrant Park or the Haçienda or a packed venue that only you and your friends remember. Sometimes the collective dance is atomised, in retreat, as it has been in the UK since 2010 as venues continue to be picked off by property developers courtesy of global hyper capitalism and profit-facing planning laws; and sometimes it’s stilled, at the lowest of low tides, during illness, anxiety or bereavement or under repressive regimes, when we retreat indoors, dancing out of sight, solo, or only in our imagination.